April 1884: A Damn Close Run Thing!

The capture of Abu Hamed by the Berber Field Force (commanded by Baker and Hicks) was something on an anti-climax. Most of the rebels fled the town as the expeditionary force approached. Less than 1000 desperate fanatics, lacking rifles or artillery support, sallied out to engage the Egyptians and were routed without delay. Imperial casualties were less than 30 men killed and wounded. The Northern District can now be considered at peace, and the threat of an attack on Egypt lifted.

Elsewhere, General Stewart advanced slowly across the Eastern desert without incident, allowing his men and horses to acclimatize, and reached the border with the Northern District by mid-April. General McNeill has pushed south from Wadi Halfa and is now encamped at Korti, in preparation for an advance through the desert to Metemma. It is understood that Stewart and McNeill intend to join forces at Atbara, prior to a punitive expedition against Osman Digna of the Hadendowa, who is believed to be encamped in the vicinity of Kassala.

Far to the south, Graham advanced across the desert, his objective being the capture of El Obeid, the last remaining major stronghold under Mahdist control. The resulting assault has been, from first reports, one of the most difficult actions ever fought against native forces and certainly one of the most costly. It is hoped that a more comprehensive account of the battle will be received in due course from Mr. Russell of the Times, who accompanied General Graham, but until then, the following brief summary must suffice:

Faced by a well-entrenched enemy, with heavy artillery and equal in size to his own, Graham advanced with the Highland and Sudanese brigades (approximately 3000 men in 4 battalions, with supporting artillery) to turn the enemy right flank by capturing the hilltop fort securing the position before assaulting the town itself from its commanding heights. The third (British) brigade (3 battalions, 2000 men supported by RN Gardner guns and the European police) under Colonel Stewart was deployed to protect the flank of this assault against enemy intervention from El Obeid itself.

Unnervingly accurate enemy artillery fire from a battery emplaced on the right, inflicted early casualties on the KRRC, but most of the enemy ‘rub appeared initially determined to hold their defensive positions and passively await the British assault.

Despite early scares (herds of goats, marriage parties and flapping washing) that slowed the advance, the assault on the enemy right flank proceeded well, encountering only limited resistance. The two Highland battalions stormed the improvised defences surrounding the fort to find them virtually undefended. Desultory rifle fire from the fort itself inflicted a few casualties as the entrenchments were traversed. It was at this point that Lieutenant Colonel Hamish McDougall of the Royal Highlanders received a fatal wound from sniper fire.

Enraged by the death of ‘Ooor wee Hammy’, the Royals surged forward, determined to storm the fort and scarcely distracted by the sight of a few friendly scouts fleeing to the rear. It was even more of a shock for the 600 Mahdist cavalry as they pursued the scouts over the crest of the hill, to encounter 800 ‘Devils in Skirts’ wielding claymore and bayonets, who ploughed into them without warning, and throwing them into immediate disarray. Over 200 Mahdists were killed in a just a few minutes fierce fighting before the cavalry broke and ran, pursued back down the hill by the enraged highlanders. More Royals were lost due to heat exhaustion and straggling than were inflicted by enemy action.

Encouraged by the example of their compatriots, the Gordons stormed the enemy artillery battery enfilading the Rifles from the hilltop, while the Xth Sudanese stormed the fort, driving out the defenders with negligible casualties. On the right, things seemed to be going well. The Royals rallied, pouring fire into the fleeing Mahdist cavalry and dispersing them completely.

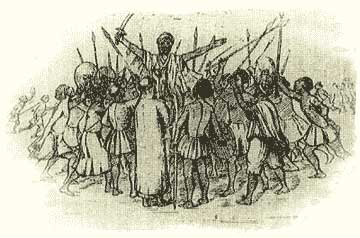

On the left, however, the situation changed rapidly. Two ‘rub of Ansar warriors (about 2500 men) advanced from the town defences to engage Stewart’s brigade, At first, the disciplined volley fire of the KRRC held the enemy at bay, inflicting heavy casualties, and killing the Emir Ibn Ben Kharzi, but that of the Yorks & Lancs was less effective. Then the Gardener on the flank jammed, the enemy was able to close and things became very desperate. The RN was overrun, the Italian police fled, and two companies of the Yorks & Lancs were overwhelmed (and their Colours captured, the first to be lost since 1879) as they sought to form a rally square. Meanwhile, a further 2500 fanatical warriors, led by the Mahdi himself, advanced on the embattled brigade, using the undulating ground to conceal their advance until the last minute. By this point, the local scouts were more interested in saving their own skins than warning of the impending assault. Stewart pulled the Royal Irish and KRRC back into a reinforced firing line, only to find much of their firepower masked by the embattled battalion to their front.

The brigade could not bring enough firepower to bear before the enemy closed, and was overwhelmed, but sold their lives dearly. Colonel Stewart was fatally wounded while fighting in the front rank of the Rifles (though some of the few survivors question his personal martial capabilities). At first ‘saved’ by a brave, unnamed (and now dead) private from ‘G’ company, he redeemed his reputation but died in the maelstrom that engulfed his command.

Graham sought to save his subordinate, pouring artillery and rifle fire from the hillside into the serried ranks of the advancing rebels but to no avail. Unknown at the time, the Mahdi came close to becoming a casualty of shrapnel fire at this stage of the battle, which influenced his subsequent actions. Within a few minutes, only small knots of men remained, desperately fighting back to back, but all were overwhelmed. Over 1500 men were killed – the worst disaster ever inflicted on a British army by native forces for over 50 years. A similar number of rebels were killed.

Back on the right, the Gordons, supported by the Royals, charged downhill, driving enemy riflemen from their entrenchments around the town. Volley fire by the Sudanese, advancing on their right, decimated the remaining Ansar ‘rub defending the town, as the Gordons took the bayonet to the last intact Jihadiyya unit. At this point, the Mahdi, having rallied his victorious division, saw that El Obeid was already taken (and aware of the likely outcome of a ‘death or glory’ charge uphill against the Sudanese brigade) ordered a general withdrawal. He and approximately 2000 warriors have retreated west, with El Fasher likely to be their intended destination.

British casualties suffered are estimated to be in excess of 1800 killed and seriously wounded – less than 250 men were found to have survived the debacle of the 3rd Brigade. (And have now been formed into a temporary composite battalion). It is estimated that over 3500 rebels were killed, and a similar number wounded.

Graham has occupied El Obeid, but will be unable to make any further offensive operations for at least one month while he tends to the wounded and reorganizes his battle-weary command.

Needless to say, Mr. Gladstone has reacted unfavourably to the news of heavy British casualties, especially as the General Election is now less than a year away. More and more, it seems that the Sudan is really ‘not worth the camels’!

In the spirit of McGonnegal – some fine Scottish purple prose

“An ode to the Sudanese”

Oh folk of Britain!, hark ye please

To the tale of the noble Sudanese,

For valour such as theirs I call,

Should never from public view fall.

‘Twas in 1884,

a doomfull year of woe and gore,

When Baker marched from Wad Hamed,

To rescue Gordon, not find him dead.

And as his army’s solid core,

Marching always to the fore,

With red tarboosh and white puttees,

Strode blue-coated Sudanese.

And day-by-day, they did not fail,

And marched oe’r sands, both hot and pale,

Until at last by Nile’s blue bight,

White walled Khartoum hove into sight.

But look! Upon the hills around,

Like ants upon the rising ground,

An army camped in noise and sound,

The Ansar horsemen stamped and grimly frowned!

And as a wave upon the shore,

Much like the Severn’s tidal bore,

They charged straight down with spear right on

Set to murder our faithful Gordon.

Now rifles roar and cannon hard-by

And noise of hooves from Baggara’s Derby

And white shirt Fellah’s flee and hide

Like walls of sand before, that fatal tide.

Now Burnaby falls to Gard’ners wail,

And troopers turn upon their tail,

And Baker’s voice does hoarsely shout.

To halt the fleeing army’s rout.

But standing fast amid the fateful wrack,

No blue coat turns ignoble back,

And with bayonet hedge and bullet strike

Sons of Sudan hold up the fight!

Now up rides Stewart on his mare

With flashing eyes and windswept hair,

And cries “ about face and fire”

Into the melee’s dreadful mire.

Ansar and Fellah tumble down

And with a cry that echoes round

Brave Sudanese the ground retake

And hold open safe retreat’s closing gate.

So at last in fading light,

A final volley shakes the night,

And Mahdi’s host called off the fight,

Leaving many for the hungry kite.

So men of empire raise a cheer,

And set a side your pint of beer,

And pray upon your bended knees,

To thank God for the Noble Sudanese!

by General Sir Gerald Graham*

(* ala Richard of the Essex Warriors).

Read On Fire & Sword in the Sudan: Epilogue.

One thought on “Fire & Sword in the Sudan: April 1884”