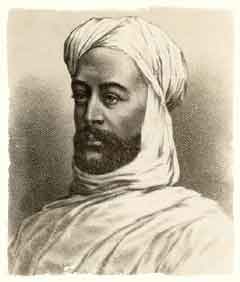

June 1883: Unrest in the Sudan

Our correspondent reports that the tribes of the Southern Sudan have risen in response to the call by the so-called Mahdi and Prophet, Mohammed Ahmed, a carpenter originally from Dongola, for a jihad against the Egyptian occupation of the Sudan. The towns of El Dueim, Jebelein and Fashoda in the far south of the country are believed to have fallen to rebel forces, their garrisons massacred or gone over to swell the ranks of the enemy.

The main rebel army, variously estimated to be between six and twelve thousand strong, is now encamped around the walls of the capital, Khartoum. Safe behind its walls, with a force of almost four thousand regulars of the Egyptian army, Generals Gordon and Hicks are confident that they can withstand a lengthy siege until a relief force is dispatched from Alexandria. General Gordon has substantially strengthened the defences with improvised mines and other obstacles. The telegraph to Atbara has been cut and steamers have been fired on while passing downstream but for now, it is still possible for messages to pass in and out of the city.

Elsewhere, the rest of the Sudan remains quiet but very tense, as the response of the Khedive to the insurrection is awaited – it will take the smallest spark to set off the powder-keg. It is probably true to say that the revolt has taken the local authorities somewhat by surprise. Captain Beresford, RN, has reinforced the defences of Suakin with a naval landing party, and anchored a gunboat in the harbour. Commandant-General Baker of the Egyptian Gendarmerie (late of the 10th Hussars) has landed at Trinkitat to evaluate the situation.

July 1883: The Sudan is Revolting!

Incited by the rabble-rousing followers of the so-called Mahdi, and encouraged by the apparent inactivity of Khedival force in June, militant tribesmen throughout the Sudan have risen to expel the hated Egyptian regime. Insurrection and atrocities have been reported in all four provinces, with Egyptian civilians murdered, their homes looted and camels violated.

In the east of the country, the inhabitants of Kassala and Atbara (the latter of great strategic importance, controlling the trade routes between the Nile and the Red Sea ports) surrendered to the insurgents as soon as they came within pistol shot of the walls, the troops of the garrison quietly discarding their uniforms and joining the rebellion.

In the west, communication has been lost with El Fasher and Dara. Of greater concern, the town of El Obeid is besieged. The governor, Sartorius Pasha, was surprised by the speed of the rebel advance from the hinterland and was unable to gather much in the way of supplies before the town was cut off. It is rumoured that he plans either to abandon the town before supplies are exhausted or strike back at the enemy before they become more powerful, as more supporters flock to the Black Standards every day.

The garrison of Khartoum stands defiantly to arms, bolstered by the conviction of General Gordon, who remains able to communicate with the outside world through smuggled messages, that speaks of good supplies, a resolute garrison and hope for speedy intervention by Mr. Gladstone. In the Northern District, Tewfiq Bey has used the few weeks of peace wisely, arresting troublemakers, preparing the garrisons and stockpiling supplies. As a result, when the storm broke, the outstanding majority of his Sudanese regulars remained loyal, the local inhabitants stayed acquiescent and the towns are well placed to withstand lengthy sieges.

Back in dear old England, Mr. Gladstone’s government remains reluctant to commit British troops to the region, despite growing popular demand to “Save Gordon”. However, there are already clear signs that British intervention is now only a matter of time – Sir Garnet Wolseley’s yacht is reported to have moved up the Nile from Alexandria to Aswan (ostensibly to view the antiquities, but more likely to better assess the strategic situation), and a large number of riverine craft are being assembled in support of future operations. Meanwhile General Graham is believed to have joined the Red Sea squadron, and junior officers of his staff have been sighted inspecting the defences of Suakin.

August 1883: Disaster at El Obeid!

Reports are coming in from the hinterland that Khedival forces have once again suffered a serious setback in the Western Sudan. The attempt by the garrison to sally out and break the siege of El Obeid was a disastrous failure. Although intelligence is limited, rumour has it that erratic rebel fire on the Egyptian cavalry acting as the vanguard almost immediately killed Sartorius Pasha as he led his men forward. Several thousand Ansar then charged headlong at the leaderless brigade. The Egyptian contingent broke and ran immediately (or fell to the ground begging for mercy, which was not forthcoming) while the Sudanese and their accompanying artillery support were overwhelmed. The cavalry were decimated attempting to cover the headlong rout back to the town and it is believed that less than 400 demoralised men (from a force of over 2000) made it back to safety. The situation in the town is now grim. With supplies exhausted, and morale low, it is now only a matter of days before the town falls, placing the whole of the Western Sudan under the control of the rebels.

Elsewhere, the number of tribesmen flocking to the Mahdist cause continues to rise – those surrounding Khartoum are now reputed to be in excess of 15,000 strong – but the rebels seem prepared to starve the besieged garrisons into submission rather than carry their defences with fire and sword.

But all is not lost: the garrison of Trinkitat has been reinforced with a further five units of Egyptian infantry, backed by a rocket troop. The town is now so full of men that an advance by General Baker must be expected shortly, before disease breaks out amongst the troops. This show of strength has also had an unexpected benefit – the local coastal Arabs of the Watusi tribe have declared their loyalty to the Egyptian administration and sent levies of troops (poor quality but welcome nonetheless) to reinforce Baker’s expedition.

The Sirdar, Sir Evelyn Wood, has sent a further unit of Egyptian infantry to Aswan, to join General Wolseley’s planned River Column. Popular pressure to send in British troops is mounting but Mr. Gladstone remains determined to resist, despite questions in the House, responding:

“The general effect being that Gordon is hemmed in – that is to say, that there are bodies of hostile troops in this neighbourhood, forming more or less a chain around it. I draw a distinction between that and a town being surrounded. It may be the opinion of the honourable Gentlemen opposite that General Gordon is in imminent danger. In our view that is an entirely erroneous opinion.”

One thought on “Fire & Sword in the Sudan: June-August 1883”